Recent reporting about the authentication of a previously unknown Amedeo Modigliani painting at the Court of Venice provides fascinating insight into the evolving field of artwork diagnostics. This was the second lost artwork by Modigliani to have hit the headlines this year, reminding art fans why the Italian sculptor and painter remains one of the most interesting artists of modern history.

Modigliani is a particularly interesting figure to consider within the field of diagnostics, in part because so many of his paintings are known, and in part because so many have been lost, found, forged, and verified over the years, spurring a huge body of research and a fair amount of controversy along the way.

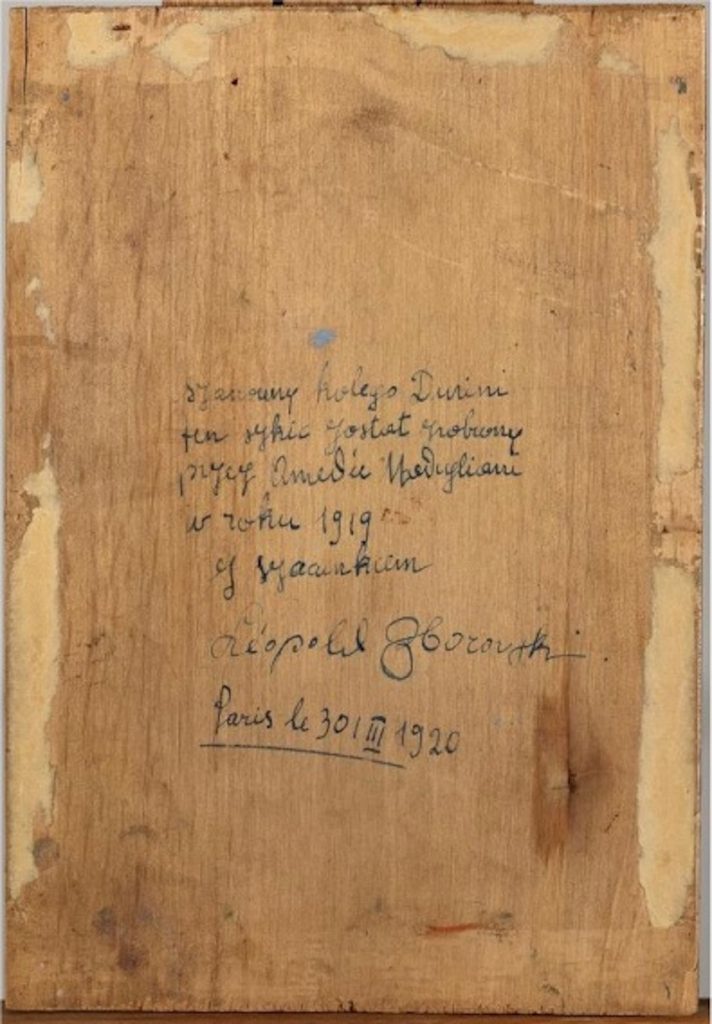

Portraying the painter’s lover Jeanne Hébuterne and featuring an inscription by the artist’s dealer Léopold Zborowski, the portrait’s analysis challenged the skill sets of a range of experts, shedding light on how modern art authentication takes place. Making this exceptional find all the more interesting, the painting completes a matching set with a larger portrait belonging to The Met in New York, for which it is believed to have been a preparatory study.

The Science of Art Authentication

Given the extraordinary value of paintings by artists as renowned as Modigliani, it is no surprise that cutting-edge technologies are enlisted to analyze and verify them. This process is particularly important for art with gaps in its provenance, such as this rediscovered portrait, which is first known to have exchanged hands in 1920, but didn’t reappear again until the 1970s when it was purchased for the equivalent of a few hundred of today’s Euros or US dollars by a collector in Venice.

Modern art diagnostics draws on tools like Ramen microscopy, which allows the materials within a composition to be examined on a molecular level. This reveals the paint types used, which can then be dated to support authentication. However, detailed historical research is also required to trace the chronology of evolving pigment use. For example, the anatase titanium white found in this and some other Modigliani paintings, while rare at the time, is now thought to have been used experimentally by the artist and his avant-garde contemporaries.

Zooming out on the artist’s process, X-ray and Infrared imaging allows exploration of the layers beneath the surface of an artwork, revealing how the paint was applied and if another composition remains underneath, as was the case for this and many other paintings by Modigliani.

The use of primers, the consistency of brushstrokes, and whether a painting was made slowly or quickly—seen from whether the paint mixed as layers were added—are all clues to be examined. These tell-tale indicators can help experts assess how closely the work matches the creative fingerprint of the artist to which it has been attributed.

A Provenance Puzzle

While some famous artworks have a known provenance detailing a chain of ownership from the moment they were painted or sculpted to the present day, many others are much more mysterious. In such cases, records from the artists and their families, estate records, historical media coverage, and artwork annotations can all help to draw missing puzzle pieces together.

As part of the authentication for this Modigliani portrait, an expert in forensic handwriting analysis was able to examine the inscription on the back of the painting, which was addressed to “Durini”, stating that the work was painted by Modigliani in 1919, and signed by the art dealer Léopold Zborowski with the date “March 30, 1920.”

Comparison with documents written and signed by Zborowski with known provenance made it possible to verify the authenticity of the inscription, while research revealed that the painting’s recipient at the time was Giuseppe Durini, Baron of Bolognano. In this way, while a stretch of the provenance of this enigmatic painting may never be known, the beginning and end of its story—so far, at least—has finally been told.