Economic cycles in the UK rarely announce themselves loudly. They tend to arrive quietly, slipping into daily life through subtle changes before most people notice the pattern forming again. A full pub on a Friday night. A mortgage offer that suddenly looks generous. Job listings multiplying in windows that were empty only a few years earlier. These are the early signals of expansion, familiar to anyone who has lived through more than one cycle.

Historically, periods of growth in the UK have often been accompanied by a sense of regained confidence rather than outright optimism. Businesses invest cautiously at first. Consumers loosen spending habits gradually. There is relief more than celebration, a feeling that things are finally moving again after a period of restraint. This cautious upswing has repeated itself across decades, whether after the early 1990s recession or the post-financial-crisis recovery of the 2010s.

The housing market has long acted as both engine and warning light. Rising prices encourage borrowing, which feeds spending, which reinforces growth. For a while, the system appears stable. Banks expand lending. Buyers stretch affordability assumptions. Policymakers reassure the public that conditions are different this time. That phrase has appeared so often in British economic history that it has almost lost its ability to reassure.

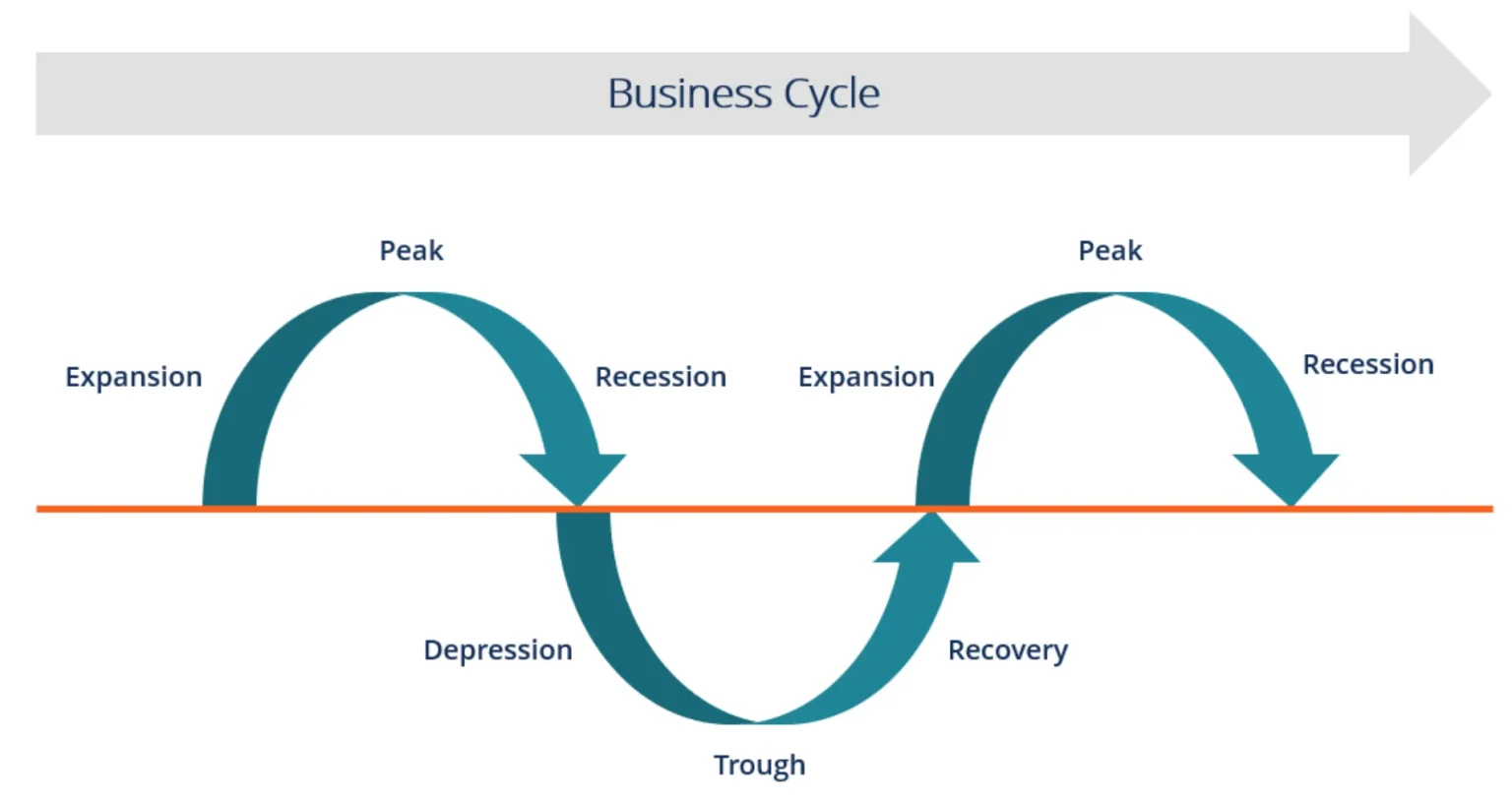

Eventually, the pressures build. Inflation creeps upward. Interest rates rise, sometimes reluctantly. Monthly repayments begin to bite. The language of everyday conversation shifts. People talk less about upgrades and more about fixing what they already have. It is rarely dramatic at first. The economy slows in pockets, then more broadly, until contraction becomes undeniable.

The downturn phase often reveals how uneven the preceding growth truly was. Certain regions feel it earlier and harder. Temporary contracts end. Retail footfall thins. Small businesses begin closing quietly rather than spectacularly. In past cycles, the UK has seen this play out repeatedly, from the industrial decline of the late 1970s to the retail contraction following the 2008 financial crisis.

Government responses follow a recognisable rhythm of their own. Initial denial gives way to emergency measures. Interest rates are cut. Spending is increased. Public messaging emphasises resilience. Later, once stability returns, the debate turns toward debt, deficits, and restraint. Austerity becomes the corrective narrative, framed as necessary discipline after excess.

One of the most striking features of UK economic cycles is how quickly collective memory fades during recoveries. Structural issues that were obvious during downturns become less urgent once growth resumes. Productivity gaps are acknowledged but postponed. Housing shortages are discussed but insufficiently addressed. The cycle continues, not because lessons were never learned, but because acting on them fully would require uncomfortable trade-offs.

The financial crisis of 2008 is often treated as exceptional, and in scale it was. Yet many of its underlying dynamics mirrored earlier episodes: cheap credit, asset inflation, regulatory complacency, and an assumption that market corrections would be mild. The aftermath, too, followed familiar lines, with years of cautious growth and lingering wage stagnation despite headline recovery.

What changes between cycles is less the pattern itself than the emotional response to it. Earlier generations associated downturns with visible industrial collapse. More recent ones experience them as prolonged uncertainty, where employment exists but security feels thin. The tools have changed — apps, dashboards, constant data — but the anxiety has not disappeared.

At one point, while rereading economic forecasts published just before a previous downturn, I was struck by how confident they sounded in retrospect, almost serene.

Another feature of historical trends in the UK is the increasing role of external shocks. Globalisation, energy markets, and geopolitical events now interact with domestic cycles more tightly than in the past. A disruption thousands of miles away can accelerate a contraction or delay a recovery. Yet even these shocks tend to plug into the same underlying rhythm rather than replacing it.

Consumers have adapted in subtle ways. Savings buffers are treated with more seriousness. Spending decisions are staggered. Large purchases are delayed until “things feel clearer.” These behavioural shifts are not new, but they have become more visible. People track the cycle intuitively now, even if they do not name it as such.

Businesses, especially small and medium-sized ones, have become more cautious in their growth assumptions. Expansion plans often include contingency clauses. Hiring is done incrementally. There is an awareness that favourable conditions rarely last as long as hoped. This realism reflects experience rather than pessimism.

UK economic cycles are not perfect loops. Each iteration leaves behind permanent changes. Some industries never fully return. Others emerge stronger. The service economy expanded where manufacturing declined. Digital infrastructure grew out of previous constraints. These shifts are layered onto the cycle rather than erasing it.

What history suggests is not inevitability but probability. Growth tends to overshoot. Corrections tend to follow. Policy responses mitigate but rarely eliminate the pattern. The cycle persists because it is rooted in human behaviour as much as in economic structures — confidence, fear, optimism, and retreat repeating in recognisable sequences.

The danger lies not in the cycle itself, but in forgetting where one stands within it. When growth feels permanent, risk multiplies. When contraction feels endless, opportunity is missed. The UK’s economic history shows that neither condition lasts as long as it seems at the time.

Understanding UK economic cycles through historical trends does not offer control, but it does offer perspective. And perspective, in economic life, is often the most valuable asset of all.